Patients are often left to their own devices when looking into cannabis and cancer, given the lack of clinical evidence, and stigma surrounding the use of the plant as medicine. Individuals who use cannabis-based medications often want to cure their cancer, not just reduce the symptoms that come with the condition. 1

So can cannabis cure cancer? The answer: Maybe!

Before we dive into the research, here’s the lowdown:

Important takeaway points on cannabis and cancer

- Your situation is unique. Every single type of cancer is a unique disease specific to one person. Even if a cannabinoid has shown promise on one cancer line, that doesn’t mean it will work for all cancers – even if it’s within the same organ system. Talk to your doctor before using cannabis to self-medicate! Work together to weigh the potential benefits and risks specific to your medical condition, and track the progress of your cancer along with your cannabis regimen.

- Use harm reduction techniques (i.e. dry herb vaporizers or edibles) to reduce potential carcinogens and respiratory symptoms when smoking cannabis.

- Avoid smoking cannabis in combination with tobacco to avoid exposure to known carcinogens.

- Advocate for the rescheduling of cannabis to improve access to cannabis for research purposes, and scientific funding for novel cannabinoid-based cancer therapies.

While we often use the term cancer to describe one disease, in reality, there are hundreds of different types of cancer, ranging from skin cancer to brain cancer and beyond. Though each type of cancer is unique, all cancers start with abnormal, rapid, and uncontrollable growth of cells. Unlike healthy cells, these abnormal cells don’t die as they are typically programmed to do, and instead begin to grow and divide uncontrollably, effectively circumventing the body’s normal checks and balances.

In certain types of cancer, these abnormal cells clump together to form a tumor. Tumors can be benign, meaning that they are non-cancerous, or they can be metastatic, meaning they are cancerous and can easily spread throughout the rest of the body. Other cancers can develop and never form a tumor, like the blood cancer leukemia – a common type of cancer in children.

How do we currently treat cancer?

Cancer therapy targets the cells that are dividing uncontrollably, while avoiding damage to the non-cancerous cells. This can be very challenging since cancer cells share the same space and DNA as the rest of the healthy cells surrounding them.

There are four main forms of cancer therapy:

- Surgery to remove cancerous tissue from the body

- Radiation therapy, which involves exposing the tumor to high doses of radiation

- Chemotherapy, which involves using drugs to kill fast-growing cancer cells and stop their growth

- Immunotherapies, which involve “training” the immune system to identify, attack and destroy cancer cells

Despite substantial progress in recent years, safe and effective treatments that will help to improve cancer outcomes, improve quality of life, and reduce the suffering of cancer patients are sorely needed. Can cannabis fill this void?

Cancer and the endocannabinoid system

The endocannabinoid system (ECS) is an important regulatory system found in nearly all cells throughout the human body. It regulates cell growth, cell survival, and cell death through the creation and breakdown of endogenous cannabinoids. The ECS is disrupted in cancerous tissues compared to healthy tissues, which means that it cannot perform its important role in maintaining the homeostasis of the tissues. Additionally, this system interacts with the immune system to play a role in the regulation of cancer growth and proliferation. So it shouldn’t be a surprise that the ECS serves as a potential target for the development of new cancer therapies. 2 3 4

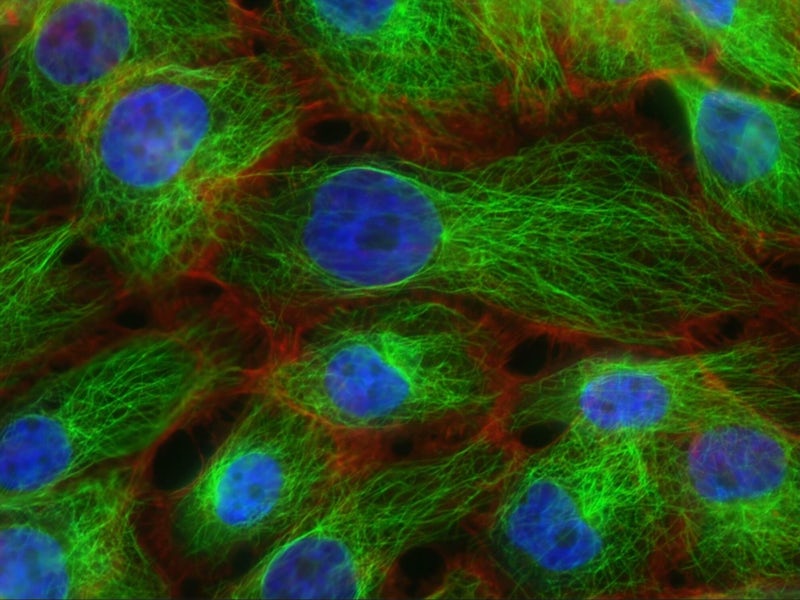

Most research investigating the effect of cannabis on cancer so far has been conducted via in vitro studies – meaning the experiment takes place outside of the living organism. These tests are performed under laboratory conditions, for example, in a petri dish.

Some research has been conducted as in vivo studies, meaning it takes place in a living organism, usually in an experimental animal model known, as preclinical research. To date, very few human clinical trials have been conducted to assess the effectiveness of THC or CBD in treating cancer. Importantly, research is underway to determine the antitumor effects of cannabinoids! 5

Some of the most intriguing work currently in progress is coming out of Technion-Israel Institute of Technology, specifically from the work of Professor David Mieri, PhD. His team is using novel techniques aimed at untangling the complex interactions between specific plant extracts with cancer cancer cells. By testing natural products or portions of them against, his team is trying to identify which components of that natural product fight types of cancer. This team is one of the leading forces in cannabis cancer research today, and aims to provide safer, more effective, personalized plant medicine. 6

THC and cancer

The main intoxicating component of cannabis, delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, aka THC, produces its effects through the ECS by activating the cannabinoid receptors (CB1 and CB2). When THC binds to the CB1 receptor, this is what produces the well-known high associated with cannabis. Dronabinol (Marinol), a synthetic form of THC, is an FDA Schedule II drug approved for treating nausea, vomiting and weight loss associated with cancer chemotherapy, supporting the role of the endocannabinoid system in cancer therapy. 7

The use of cannabis as a cancer treatment was popularized by Rick Simpson, a medical cannabis advocate. Simpson claimed that he could cure his skin cancer using a homemade, full-spectrum cannabis extract that’s high in THC. The extract, which has come to be known as Rick Simpson Oil (RSO), is highly potent, dense, and usually administered orally, sublingually, or topically. While RSO has been subject to increased popularity in treating certain types of cancers, no clinical trials have tested the safety or efficacy of RSO in humans, meaning that all evidence is anecdotal.

In vitro and in vivo studies on THC and cancer

THC can induce cell death in various cancer cell lines and experimental animal models, an important role in cancer treatment.

- THC was found to reduce cancer cell growth and induced cell death in human glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) cells. GBM is a rare but aggressive brain cancer with very limited treatment options. 8

- THC induced cell death in three leukemia cell lines and human colorectal cancer cells and induced cell death and loss of cell viability in a melanoma cell culture and experimental animal model. 9 10 11

Human studies on THC and cancer

To date only small pilot studies have been conducted assessing the effectiveness of THC in treating cancer in humans. For example, in two small pilot studies, THC administration directly in the tumor of patients with terminal brain cancer reduced tumor growth and helped to improve clinical symptoms. We will have to wait for objective clinical evidence to determine THC’s effectiveness as an anticancer agent. 12 13

CBD and cancer

Cannabidiol (CBD) is the most abundant non-intoxicating phytocannabinoid associated with the cannabis plant. Although CBD itself is not made by the plant (it is a derivative of CBDA), there is increasing evidence that it has the potential to treat several different types of cancer.

Preclinical research on CBD and cancer

A growing body of research suggests that CBD can induce cell death and reduce cell growth in human breast, prostate, colorectal, gastric, leukemia, and glioma cancer cell lines. Two studies in particular indicated that CBD can induce lung cancer cell death 14, and reduce the spread and growth of rat thyroid cancer cells. 15 16 17 18 19

CBD has been investigated for its potential to treat a variety of cancers showing promising results in experimental animal models. 20

The cannabinoid was found to:

- slow the growth of human breast cancer cells in experimental animal models and reduce cancer spread 21 22

- induce cell death of human leukemia cells in experimental animal models 23

- slow the spread of human lung cancer cells in an experimental animal model 24

- slow the development of polyps and tumors in a mouse model of colon cancer 25

Human studies on CBD and cancer

In one of the earliest cannabinoid first randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized Phase I clinical trials, CBD treatment improved physical and psychological well-being in patients with advanced cancers in palliative care. 26

While preliminary evidence is promising, we’ll need to wait for further clinical trial results to determine the efficacy of THC and CBD in treating various cancers. Importantly, there are dozens of clinical trials underway, many of which are even researching CBD in human subjects. We will continue to learn more about CBD’s cancer fighting potential in the near future.

What about combining THC and CBD to treat cancer?

Preclinical studies

Although most research has focused on assessing one specific phytocannabinoid, primarily THC or CBD, there is evidence to suggest that whole cannabis extracts (ie full spectrum) may be more effective in killing cancer cells 27

- A 2018 study found that a whole cannabis plant extract was more effective than pure THC in producing an anti-tumor response in a breast cancer cell culture and animal model. 28

- In 2011, researchers found that a combination treatment of CBD and THC reduced the ability of brain cancer cells to survive and grow while also promoting brain cancer cell death. 29

- In the same study, CBD and THC, in combination with temozolomide (a pharmaceutical chemotherapy agent), was found to reduce the growth and increase the death of certain brain cancers tumors in an experimental animal model.

- CBD has been reported to enhance the ability of THC to reduce GBM cell growth and survival. 30

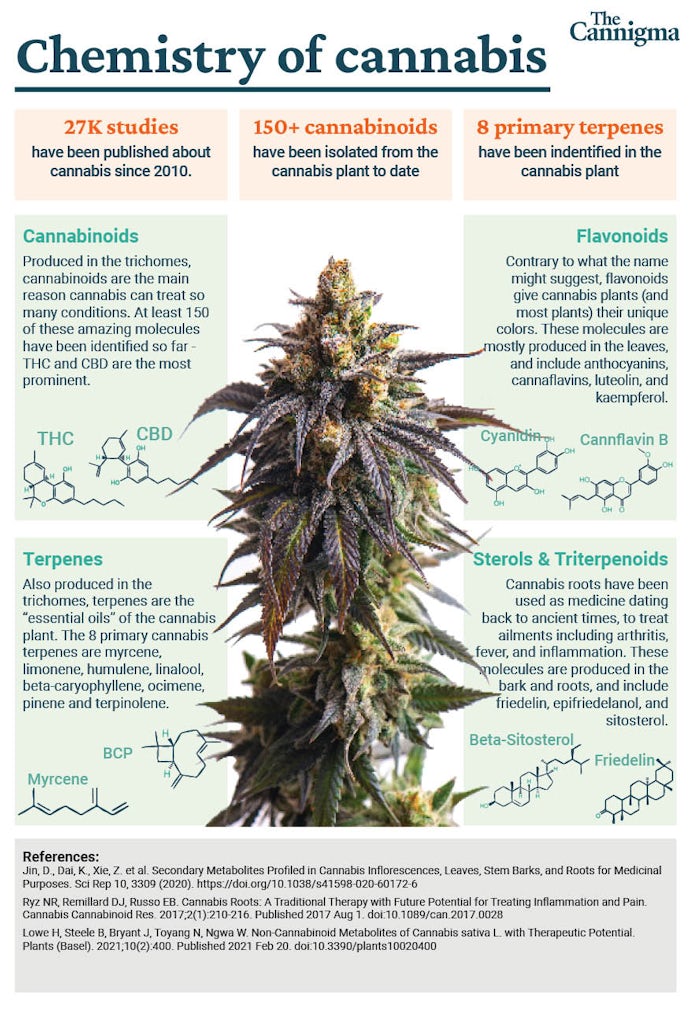

- Other compounds in the cannabis plant, known as terpenoids and flavonoids, have been reported to exhibit anti-cancer properties. 31 32 33

Together, these findings suggest that when it comes to cannabis as a cancer therapy, the whole might be greater than the sum of its parts.

Clinical studies

Minimal studies have investigated the therapeutic potential of THC or CBD in treating cancer in human subjects.

- A 2019 study indicates that CBD improves survival rates in patients with GBM 34

- Based on the promising findings from the preclinical studies mentioned above, CBD:THC (1:1 ratio) in combination with temozolomide was investigated for its therapeutic ability in the treatment of GBM. 35

- CBD:THC treatment in combination with temozolomide was found to increase the survival rate in patients with recurrent GBM compared to temozolomide treatment alone (83% vs. 44%), which represents an increase in the survival rate of almost 12 months.

- These findings were corroborated in a 2019 study, where CBD: THC in combination with temozolomide increased the survival rate compared to placebo (83% vs. 56%). 36

Synthetic (pharmaceutical) cannabinoids and cancer

Scientists did not rest when they learned that cannabis and cannabinoids may have anti cancer properties. Instead, since the 1980s, scientists have been working on leveraging what we know about the ECS and cannabinoid chemistry to create new drugs that don’t exist naturally. This process is known as drug development, and has been critical to our understanding of the ECS and cannabis medicine.

There are now hundreds of these synthetic cannabinoids that have been developed and many are being trialed for their utility in combating numerous types of cancer, many with very promising early results. But unlike CBD and THC, synthetic cannabinoids are man-made, do not have thousands of years of documented medical use, and must undergo years (or even decades) of rigorous testing before they can be approved for use in humans. 37 38

In most of the studies mentioned above, evidence assessing the ability of CBD and THC to act as an anticancer agent come from synthetically-derived pharmaceutical grade formulations. This is due to the lack of availability of dispensary products in the research setting. Only recently (2022) have laws governing cannabis research in the US become less restrictive. So until now, we have been missing an important area of research, which is real world data of people using cannabinoids. As regulations continue to loosen, scientists are finally able to begin gathering this data

Many cancer patients may choose to self-medicate using cannabinoid based products available at local dispensaries, and may use various routes of administration (i.e. inhalation vs edible) on which we lack clinical data. Hopefully, these changes to legislation will result in rigorous scientific trials assessing the potential anticancer effects of these consumer cannabis products, not just pharmaceutical grade isolates.

Does cannabis cause cancer?

Until now, we have focused on the potential therapeutic effects of cannabinoids like THC and CBD in cancer treatment. But there is also evidence indicating that cannabis may be associated with certain cancers, and may even make certain types of cancer worse.

There is no clear answer to the question: does cannabis cause cancer? Humans do not live under controlled conditions, so it’s often impossible to determine what came first; we have a chicken and egg problem! For example, some consumers smoke tobacco in combination with cannabis, which muddies the water when assessing the relationship between cannabis and cancer.

Interestingly, the relationship between cannabis smoke and lung cancer is not reported when controlling for tobacco use. This doesn’t mean that cannabis smoke does not contain carcinogens. Indeed, cannabis smoke contains more carcinogens than tobacco smoke. However recent data suggests that cannabis use may be underreported in lung cancer patients, and that the use of cannabis and tobacco in combination may result in more severe and advanced forms of lung cancer. 39 40 41

One recent synthesis of studies suggests that cannabis use may reduce the risk for certain types of non-testicular cancer. Importantly, this synthesis did not assess cannabis use and the overall risk of cancer. 42

Does cannabis use make certain types of cancer worse?

Some studies suggest that the use of cannabis by cancer patients undergoing immunotherapy is associated with reduced clinical outcomes. Cannabis consumption reduced treatment response in patients with advanced skin cancer undergoing immunotherapy. Patients who did not use cannabis were 3.17 times more likely to respond to treatment than cannabis users. Additionally, cannabis consumption by cancer patients being treated with immunotherapy has been associated with reduced time to tumor progression and overall survival. While alarming, this is not completely surprising. Cannabis and THC have well established interactions with the immune system, and altering the immune system when it is being manipulated intentionally to fight cancer may interfere with the intended effects. 43 44

Together, these findings suggest that the context under which cannabis is used matters and, at times, may result in negative clinical outcomes. The relationship between cannabis and cancer is complex because it is influenced by several factors, including the type of cancer, the treatment being used, and the patient’s unique situation. Added to that, the ECS is complex and is uniquely intertwined with each cancer, which means that while one cannabinoid may be useful for one cancer, it may not be helpful or could even worsen another.

The lack of available human clinical trials is concerning, and more research is needed to tease out how exactly to use cannabis to combat cancer. However, the available data shows promise for using cannabinoids in cancer therapeutics, both to treat the symptoms of chemotherapy, and also as a potential target for the treatment of the cancer itself.

Sources

- Buchwald, D., Brønnum, D., Melgaard, D., & Leutscher, P. D. (2020). Living with a hope of survival is challenged by a lack of clinical evidence: an interview study among cancer patients using cannabis-based medicine. Journal of palliative medicine, 23(8), 1090-1093.

- Falasca, V., & Falasca, M. (2022). Targeting the Endocannabinoidome in Pancreatic Cancer. Biomolecules, 12(2), 320.

- Fraguas-Sánchez, A. I., Fernández-Carballido, A., Simancas-Herbada, R., Martin-Sabroso, C., & Torres-Suárez, A. I. (2020). CBD loaded microparticles as a potential formulation to improve paclitaxel and doxorubicin-based chemotherapy in breast cancer. International journal of pharmaceutics, 574, 118916.

- Braile, M., Marcella, S., Marone, G., Galdiero, M. R., Varricchi, G., & Loffredo, S. (2021). The interplay between the immune and the endocannabinoid systems in cancer. Cells, 10(6), 1282.

- Baram, L., Peled, E., Berman, P., Yellin, B., Besser, E., Benami, M., … & Meiri, D. (2019). The heterogeneity and complexity of Cannabis extracts as antitumor agents. Oncotarget, 10(41), 4091.

- Procaccia, S., Lewitus, G. M., Lipson Feder, C., Shapira, A., Berman, P., & Meiri, D. (2022). Cannabis for Medical Use: Versatile Plant Rather Than a Single Drug. Frontiers in pharmacology, 13, 894960. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.894960

- Gaisey, J., & Narouze, S. N. (2021). Dronabinol (Marinol®). In Cannabinoids and Pain (pp. 105-107). Springer, Cham.

- McAllister, S. D., Soroceanu, L., & Desprez, P. Y. (2015). The antitumor activity of plant-derived non-psychoactive cannabinoids. Journal of neuroimmune pharmacology, 10(2), 255-267.

- Powles, T., Poele, R. T., Shamash, J., Chaplin, T., Propper, D., Joel, S., … & Liu, W. M. (2005). Cannabis-induced cytotoxicity in leukemic cell lines: the role of the cannabinoid receptors and the MAPK pathway. Blood, 105(3), 1214-1221.

- Greenhough, A., Patsos, H. A., Williams, A. C., & Paraskeva, C. (2007). The cannabinoid δ9‐tetrahydrocannabinol inhibits RAS‐MAPK and PI3K‐AKT survival signalling and induces BAD‐mediated apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells. International journal of cancer, 121(10), 2172-2180.

- Armstrong, J. L., Hill, D. S., McKee, C. S., Hernandez-Tiedra, S., Lorente, M., Lopez-Valero, I., … & Lovat, P. E. (2015). Exploiting cannabinoid-induced cytotoxic autophagy to drive melanoma cell death. Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 135(6), 1629-1637.

- Guzman, M., Duarte, M. J., Blazquez, C., Ravina, J., Rosa, M. C., Galve-Roperh, I., … & González-Feria, L. (2006). A pilot clinical study of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol in patients with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. British journal of cancer, 95(2), 197-203.

- Kenyon, J., Liu, W. A. I., & Dalgleish, A. (2018). Report of objective clinical responses of cancer patients to pharmaceutical-grade synthetic cannabidiol. Anticancer Research, 38(10), 5831-5835.

- Haustein, M., Ramer, R., Linnebacher, M., Manda, K., & Hinz, B. (2014). Cannabinoids increase lung cancer cell lysis by lymphokine-activated killer cells via upregulation of ICAM-1. Biochemical pharmacology, 92(2), 312-325.

- Gallily, R., Even-Chen, T., Katzavian, G., Lehmann, D., Dagan, A., & Mechoulam, R. (2003). γ-Irradiation enhances apoptosis induced by cannabidiol, a non-psychotropic cannabinoid, in cultured HL-60 myeloblastic leukemia cells. Leukemia & lymphoma, 44(10), 1767-1773.

- Massi, P., Vaccani, A., Ceruti, S., Colombo, A., Abbracchio, M. P., & Parolaro, D. (2004). Antitumor effects of cannabidiol, a nonpsychoactive cannabinoid, on human glioma cell lines. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 308(3), 838-845.

- Ligresti, A., De Petrocellis, L., & Di Marzo, V. (2016). From phytocannabinoids to cannabinoid receptors and endocannabinoids: pleiotropic physiological and pathological roles through complex pharmacology. Physiological reviews.

- Ligresti, A., Moriello, A. S., Starowicz, K., Matias, I., Pisanti, S., De Petrocellis, L., … & Di Marzo, V. (2006). Antitumor activity of plant cannabinoids with emphasis on the effect of cannabidiol on human breast carcinoma. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 318(3), 1375-1387.

- Lee, C. Y., Wey, S. P., Liao, M. H., Hsu, W. L., Wu, H. Y., & Jan, T. R. (2008). A comparative study on cannabidiol-induced apoptosis in murine thymocytes and EL-4 thymoma cells. International immunopharmacology, 8(5), 732-740.

- Simmerman, E., Qin, X., Jack, C. Y., & Baban, B. (2019). Cannabinoids as a potential new and novel treatment for melanoma: a pilot study in a murine model. Journal of Surgical Research, 235, 210-215.

- Ligresti, A., Moriello, A. S., Starowicz, K., Matias, I., Pisanti, S., De Petrocellis, L., … & Di Marzo, V. (2006). Antitumor activity of plant cannabinoids with emphasis on the effect of cannabidiol on human breast carcinoma. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 318(3), 1375-1387.

- McAllister, S. D., Christian, R. T., Horowitz, M. P., Garcia, A., & Desprez, P. Y. (2007). Cannabidiol as a novel inhibitor of Id-1 gene expression in aggressive breast cancer cells. Molecular cancer therapeutics, 6(11), 2921-2927.

- McKallip, R. J., Jia, W., Schlomer, J., Warren, J. W., Nagarkatti, P. S., & Nagarkatti, M. (2006). Cannabidiol-induced apoptosis in human leukemia cells: a novel role of cannabidiol in the regulation of p22phox and Nox4 expression. Molecular Pharmacology, 70(3), 897-908.

- Ramer, R., & Hinz, B. (2017). Cannabinoids as anticancer drugs. Advances in Pharmacology, 80, 397-436.

- Izzo, A. A., & Camilleri, M. (2009). Cannabinoids in intestinal inflammation and cancer. Pharmacological Research, 60(2), 117-125.

- Good, P., Haywood, A., Gogna, G., Martin, J., Yates, P., Greer, R., & Hardy, J. (2019). Oral medicinal cannabinoids to relieve symptom burden in the palliative care of patients with advanced cancer: A double-blind, placebo controlled, randomised clinical trial of efficacy and safety of cannabidiol (CBD). BMC palliative care, 18(1), 1-7.

- Baram, L., Peled, E., Berman, P., Yellin, B., Besser, E., Benami, M., … & Meiri, D. (2019). The heterogeneity and complexity of Cannabis extracts as antitumor agents. Oncotarget, 10(41), 4091.

- Blasco-Benito, S., Seijo-Vila, M., Caro-Villalobos, M., Tundidor, I., Andradas, C., García-Taboada, E., … & Sánchez, C. (2018). Appraising the “entourage effect”: Antitumor action of a pure cannabinoid versus a botanical drug preparation in preclinical models of breast cancer. Biochemical pharmacology, 157, 285-293.

- Torres, S., Lorente, M., Rodríguez-Fornés, F., Hernández-Tiedra, S., Salazar, M., García-Taboada, E., … & Velasco, G. (2011). A combined preclinical therapy of cannabinoids and temozolomide against glioma. Molecular cancer therapeutics, 10(1), 90-103.

- Marcu, J. P., Christian, R. T., Lau, D., Zielinski, A. J., Horowitz, M. P., Lee, J., … & McAllister, S. D. (2010). Cannabidiol Enhances the Inhibitory Effects of Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol on Human Glioblastoma

- Huang, M., Lu, J. J., Huang, M. Q., Bao, J. L., Chen, X. P., & Wang, Y. T. (2012). Terpenoids: natural products for cancer therapy. Expert opinion on investigational drugs, 21(12), 1801-1818.

- Abotaleb, M., Samuel, S. M., Varghese, E., Varghese, S., Kubatka, P., Liskova, A., & Büsselberg, D. (2018). Flavonoids in cancer and apoptosis. Cancers, 11(1), 28.

- Tomko, A. M., Whynot, E. G., Ellis, L. D., & Dupré, D. J. (2020). Anti-cancer potential of cannabinoids, terpenes, and flavonoids present in cannabis. Cancers, 12(7), 1985.

- Likar, R., Koestenberger, M., Stultschnig, M., & Nahler, G. (2019). Concomitant treatment of malignant brain tumours with CBD–a case series and review of the literature. Anticancer Research, 39(10), 5797-5801.

- Dumitru, C. A., Sandalcioglu, I. E., & Karsak, M. (2018). Cannabinoids in glioblastoma therapy: new applications for old drugs. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience, 159.

- Twelves, C., Short, S., Wright, S., & Cannabinoid in Recurrent Glioma Study Group. (2017). A two-part safety and exploratory efficacy randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled study of a 1: 1 ratio of the cannabinoids cannabidiol and delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (CBD: THC) plus dose-intense temozolomide in patients with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme (GBM).

- Fraguas-Sánchez, A. I., Fernández-Carballido, A., & Torres-Suárez, A. I. (2016). Phyto-, endo- and synthetic cannabinoids: promising chemotherapeutic agents in the treatment of breast and prostate carcinomas. Expert opinion on investigational drugs, 25(11), 1311–1323. https://doi.org/10.1080/13543784.2016.1236913

- Raup-Konsavage, W. M., Johnson, M., Legare, C. A., Yochum, G. S., Morgan, D. J., & Vrana, K. E. (2018). Synthetic Cannabinoid Activity Against Colorectal Cancer Cells. Cannabis and cannabinoid research, 3(1), 272–281. https://doi.org/10.1089/can.2018.0065

- Huang, Y. H. J., Zhang, Z. F., Tashkin, D. P., Feng, B., Straif, K., & Hashibe, M. (2015). An epidemiologic review of marijuana and cancer: an update. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 24(1), 15-31.

- Moir, D., Rickert, W. S., Levasseur, G., Larose, Y., Maertens, R., White, P., & Desjardins, S. (2008). A comparison of mainstream and sidestream marijuana and tobacco cigarette smoke produced under two machine smoking conditions. Chemical research in toxicology, 21(2), 494-502.

- Betser, L., Glorion, M., Mordant, P., Caramella, C., Ghigna, M. R., Besse, B., … & Pradere, P. (2021). Cannabis use and lung cancer: time to stop overlooking the problem?. European Respiratory Journal, 57(5).

- Clark, T. M. (2021). Scoping Review and Meta-Analysis Suggests that Cannabis Use May Reduce Cancer Risk in the United States. Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research, 6(5), 413-434.

- Taha, T., Meiri, D., Talhamy, S., Wollner, M., Peer, A., & Bar‐Sela, G. (2019). Cannabis impacts tumor response rate to nivolumab in patients with advanced malignancies. The oncologist, 24(4), 549-554.

- Bar-Sela, G., Cohen, I., Campisi-Pinto, S., Lewitus, G. M., Oz-Ari, L., Jehassi, A., … & Meiri, D. (2020). Cannabis consumption used by cancer patients during immunotherapy correlates with poor clinical outcome. Cancers, 12(9), 2447.

Sign up for bi-weekly updates, packed full of cannabis education, recipes, and tips. Your inbox will love it.

Shop

Shop Support

Support